Defensive Nixos (1/3) - Intro

Here’s a distribution that can still be considered “niche”. And yet, NixOS (along with a few more modest projects of the same kind) it is getting more and more attention. You may have already come across the name of this Linux distribution in a Hacker News comment or during a chat with a somewhat quirky colleague. (You know, the unbearable free software enthusiast who always corrects you on the definition of “open source” and “DevOps” and who installs a new OS every weekend).

NixOS has been my main working tool for the past 3 years. Despite its young age (first usable version around 2013), its advantages in terms of robustness, maintainability, and security are, in my opinion, unmatched.

Many organizations would benefit from deploying this type of technology on a large scale. That’s why I’m starting a small series of articles on the topic. Even without a complete infrastructure overhaul, I believe the concept of functional deployment, which we’ll be discussing, is an excellent source of inspiration for those working in infrastructure development and maintenance.

The first few articles will mostly revisit what I presented in my talk on the topic at the 2022 Hack’it’N conference.

Of course, explaining the detailed workings of NixOS in just a few articles is ambitious at least. Especially since the excellent Nix Pills already exist. These articles, written by one of the main contributors to the NixOS community, are of exceptional quality and serve as the go-to gateway into the depths of the beast.

My goal is a bit different. With these articles, I want to address blue teams, ops, secops, devsecops, CISOs, and all the other complicated names for: cybersecurity engineer. NixOS, and the everything-as-code philosophy that inspired it, are, I’m convinced, the building blocks and mortar of the cyber fortresses of tomorrow.

So, I invite you to join me on this journey to discover NixOS and its advantages in terms of cybersecurity.

Technical Challenges

Before introducing the technology, I want to start by highlighting a few issues that I believe will resonate with many of you. These problems have caused numerous security incidents (or have at least significantly contributed to them) to the point where entire job roles have been created to address them.

Incomplete Mapping: this, to me, is the most critical point. Modern information systems are becoming increasingly complex. The visibility that administrative teams have over their infrastructures is often very poor. It’s hard to tell which machines are deployed, in which data center, and what’s installed on them. This is a real problem for the maintainability of IT environments and, consequently, for network security.

Configuration Entropy: besides the lack of traceability on configurations, it’s also very difficult to find standards.

In the oldest information systems I’ve seen, there were usually as many configuration practices as there were different deployments.

Each administrator has their habits and preferences.

The same application might be deployed one day using a pip package and the next by extracting an archive into /opt.

Whether for maintainability or incident response, without standardization, the job of an ops professional quickly becomes a nightmare.

Chaotic Patch Management: since configurations are chaotic, applying a security patch can quickly become a Herculean task. Even when applying the patch is straightforward, the lack of visibility prevents any certainty about its robustness. Every infrastructure deployment is usually accompanied by a deep-seated fear of encountering incompatibilities that weren’t discovered in pre-production.

Opaque Auditing: in my current work, I’ve found that auditing a system is often more complicated than it should be. It usually boils down to one of three methods: commenting on an architectural diagram that is often outdated; analyzing a handful of configuration files (out of context and not representative of most of the infrastructure); or conducting pentesting exercises that are far from exhaustive.

Complex Automation: it’s easy to back up the contents of a database or the source code of an application to restore them in case of an incident. Restoring an entire infrastructure with its virtual machines, their file systems, and their exact configurations is much harder. Deployment procedures, which are supposed to be the safeguard in such scenarios, are often considered incomplete or outdated.

State of the Art

In general, the first attempts at infrastructure automation and standardization “as code” are made using scripts and/or GPOs. This solution is obviously not very robust, and while it’s easy to set up for small networks, it’s far from scalable. Often, scripts are transferred via USB drives, email, or stored on a network share (I can hear CISOs coughing). Version control is almost non-existent, and attempts at standardization are doomed to fail.

As the network grows, the teams become more mature (and when a CIO decides to allocate some budget), we start seeing the emergence of infrastructure as code. Implementing IaC can sometimes be a bit experimental, but it’s generally a big step towards IT resilience. However, regardless of the technology used (Ansible, Terraform, SaltStack, etc.), they rely on a virtual state of the system. Any manual change made by an admin that isn’t reflected in the code can lead to hours, or even days, of debugging. Those who have written Ansible playbooks know that a significant part (sometimes the majority) of the time can be spent making those playbooks idempotent.

Finally, we have containers. Of course, this technology solves many of the problems we’ve mentioned above. However, this solution isn’t applicable everywhere, especially when it comes to maintaining physical infrastructures.

The Perfect System

Well, let’s humbly list the characteristics of a perfect infrastructure as code system based on what we’ve seen:

- Automatable: an easy-to-handle toolchain should allow for the precise automation of system installation, without human intervention.

- Versionable: it must be possible to fully version the system configuration (in addition to snapshots, which should only concern data).

- Auditable: reading the code/configuration file should leave no doubt about the exact configuration of the system as deployed.

- Full-Featured: all the functionalities of a classic automation system (e.g., Ansible) should be present.

- Reproducible & Idempotent: updates and/or redeployments must be deterministic and strictly idempotent.

Basic Concepts

Nix Package Manager: Derivation > Package

It all started in 2006 with a publication by Eelco Dolstra.

He outlines the main problems with traditional package managers, particularly the increasing difficulty of managing dependencies (e.g., cyclic dependencies) and sensitivity to breaking changes. To address these issues, he proposes a new model inspired by functional programming languages.

In his model, packages must possess the same properties found in functional programming:

- Immutability: once installed, a package cannot be modified.

- Isolation: similar to functions, the installation of a package should not affect the execution of others.

- Determinism: all dependencies are exhaustively identified, and installations must be idempotent.

A package with these properties is called a derivation.

This fundamentally changes the traditional approach to system administration. With all due respect to the Debian distribution and everything it has brought to the open-source world, dpkg is a nightmare to work with. Its history doesn’t do it any favors.

Thanks to the principle of derivation, you can forget about obscure packages that mix unknown build systems, esoteric scripts, and mystical environment variables. Derivation definitions are written in a clear syntax that is accessible even to novices.

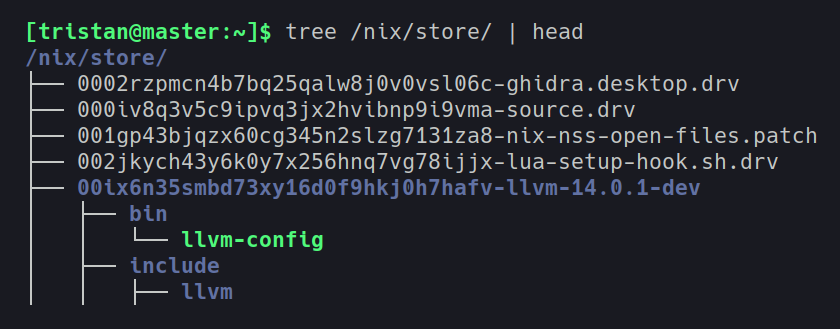

Nix Store

To continue the parallel with Debian, take a .deb package.

Once installed, the package scatters a bunch of files all over the system

(binaries in /usr/bin, libraries in /var/lib, etc.).

Even though there’s a semblance of order and tools have been created to facilitate management, it’s still tedious to know exactly which package is responsible for a given file

(not to mention the conflicts when two packages want to overwrite the same file).

With NixOS, there’s no need to hunt for where files are and who they belong to.

Everything (or almost everything) is stored in /nix/store (as in the example above with LLVM).

Here, each derivation is represented by a hash.

To simplify, this hash is the concatenation of all the sources needed to build the package and the hashes of all the derivations it depends on.

HASH_DERIVATION ~= hash( hash(SOURCES) + hash(DEPENDANCES) )

This mechanism guarantees the integrity and total immutability of all packages and their dependencies, down to the most basic components (somewhat like a blockchain for crypto enthusiasts). You can also forget about name collision issues, whether by accident (two packages having the same name) or due to an attacker trying to have fun with path hijacking and other mischief.

Connecting the Dots

To clarify how the Nix store works, let’s take a specific example. On my machine, I have GCC installed.

[tristan@demo:~]$ gcc --version

gcc (GCC) 11.3.0

To run GCC, my shell searched for the binary in the PATH and found it in a .nix-profile folder in my home directory.

[tristan@demo:~]$ which gcc

/home/tristan/.nix-profile/bin/gcc

This file is just a link to the Nix store, which actually contains the binary. This whole chain is instantiated at startup for each user, depending on the binaries they are supposed to access.

[tristan@demo:~]$ ls -l /home/tristan/.nix-profile/bin/gcc

/home/tristan/.nix-profile/bin/gcc -> /nix/store/ykcrnkiicqg1pwls9kgnmf0hd9qjqp4x-gcc-wrapper-11.3.0/bin/gcc

Let’s dig even deeper to examine the content of this GCC file. (The middle of the file is intentionally censored because it’s very long and complex.)

#! /nix/store/c24i2kds9yzzjjik6qdnjg7a94i9pp05-bash-5.2-p15/bin/bash

set -eu -o pipefail +o posix

shopt -s nullglob

if (( "${NIX_DEBUG:-0}" >= 7 )); then

set -x

fi

path_backup="$PATH"

source /nix/store/zd2viirgdm4ffgipgpslmysmlzs6fscb-gcc-wrapper-12.3.0/nix-support/utils.bash

[...]

# if a cc-wrapper-hook exists, run it.

if [[ -e /nix/store/zd2viirgdm4ffgipgpslmysmlzs6fscb-gcc-wrapper-12.3.0/nix-support/cc-wrapper-hook ]]; then

compiler=/nix/store/dfqlrp0zgq8k21qajn7z6d0yjn9ab9af-gcc-12.3.0/bin/gcc

source /nix/store/zd2viirgdm4ffgipgpslmysmlzs6fscb-gcc-wrapper-12.3.0/nix-support/cc-wrapper-hook

fi

if (( "${NIX_CC_USE_RESPONSE_FILE:-0}" >= 1 )); then

responseFile=$(mktemp "${TMPDIR:-/tmp}/cc-params.XXXXXX")

trap 'rm -f -- "$responseFile"' EXIT

printf "%q\n" \

${extraBefore+"${extraBefore[@]}"} \

${params+"${params[@]}"} \

${extraAfter+"${extraAfter[@]}"} > "$responseFile"

/nix/store/dfqlrp0zgq8k21qajn7z6d0yjn9ab9af-gcc-12.3.0/bin/gcc "@$responseFile"

else

exec /nix/store/dfqlrp0zgq8k21qajn7z6d0yjn9ab9af-gcc-12.3.0/bin/gcc \

${extraBefore+"${extraBefore[@]}"} \

${params+"${params[@]}"} \

${extraAfter+"${extraAfter[@]}"}

fi

The first thing we notice is that it’s still not the GCC binary itself, but a Bash wrapper. This wrapper’s role is to prepare the runtime environment for GCC by providing all the necessary libraries, tools, and scripts directly from the Nix store.

The second important point is the presence of absolute paths for all commands used.

Thanks to this mechanism, each dependency is identified, and no path resolution is left to chance or vague conventions.

In short, at NixOS, it’s configuration over convention, and that’s a good thing.

Of course, such a script is not easily readable and is never written by hand. In the next article, we’ll see how the original Nix code is structured to generate this type of file.

Mirror, Mirror on the Web

As we saw earlier, the equivalent of a package in the Nix universe is the derivation. Of course, a derivation doesn’t resemble a package at all. A common problem for distributions adopting a new package manager is the difficulty of recreating a sufficiently comprehensive package library. The reason: the need to repackage all programs, set up a complete infrastructure for mirrors, and establish a QA process (protecting and versioning LTS / stable / testing / unstable branches, etc.).

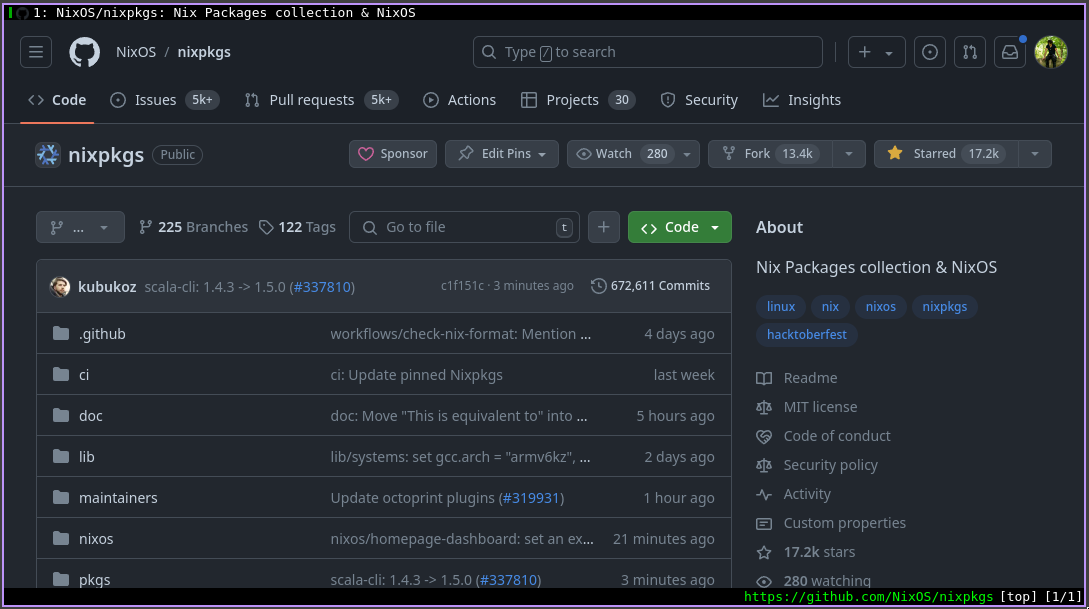

The great strength of NixOS, even beyond what has been mentioned earlier, is the declarative and functional language on which Nix is built. This functional language is called… Nix… just like the package manager (a questionable choice, indeed, but if developers were poets, we’d know it). However, the simplicity and elegance of this language have remarkably simplified the writing of derivations, to the point that the repackaging problem has been resolved with surprising speed.

Today, NixOS is the distribution that offers the largest number of different packages (over 100,000 as I write this).

And to solve the infrastructure issue, since everything is defined in the same programming language, there’s no need for a dedicated mirror. The NixOS mirror is simply the nixpkgs repository on GitHub.

The more discerning among you may have noticed the impressive number of issues and pull requests in the project. Indeed, this is a symptom of the simplicity of development, as well as the success and interest that the distribution generates. If the project interests you, contribute to it. It’s the best way to learn!

System as Code

As we’ve seen, all packages are written in the same functional language.

But that’s not all. In NixOS, the entire system can be represented in Nix.

This principle of system as code is probably what primarily attracts people to the distribution.

However, I won’t delve into the syntax of Nix today; that will be the subject of the next article!